I often see this 10-volume set in restaurants, cafés and pubs where books are used to line shelves, and in second-hand bookshops too, usually for a knock-down price. When we were a young family in the early 1960s, my parents bought the entire 24-volume set of the red-and black-liveried Collier’s Encyclopaedia, with its volumes ‘A to Ameland, Amen to Artillery, Art Nouveau to Beetle’ and so on. This 10-volume set of Junior Classics came with them. Collier’s was an excellent encyclopaedia, and if it reflected an American world-view, it was an even-handed, optimistic and inclusive one, a breath of fresh air. Anything was possible and life was good and everybody was equal. I was gifted the Junior Classics when my parents moved to a smaller house.

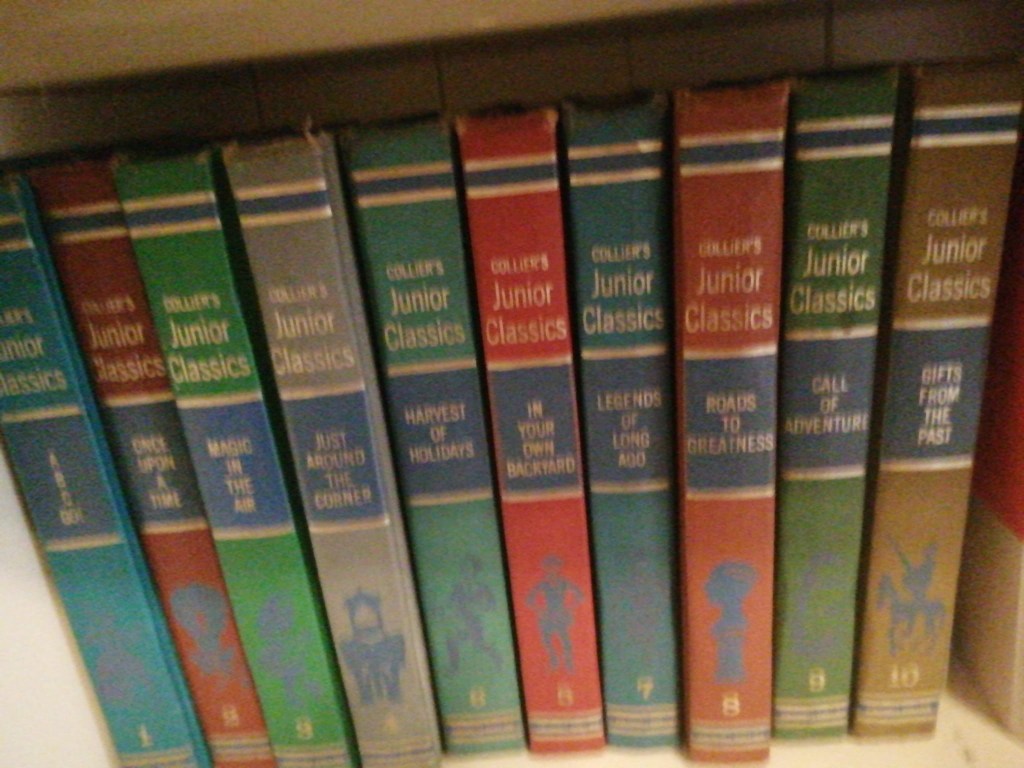

The ten volumes, published in 1962, are titled ABC Go! Once Upon A Time, Magic In The Air, Just Around The Corner, In Your Own Backyard, Harvest of Holidays, Legends of Long Ago, Roads To Greatness, Call of Adventure, Gifts From The Past. They are all anthologies, and all the anthologised matter has the illustrations of the original editions, some in black and white, some in gorgeous colour. Just to take a few examples: a poem by Langston Hughes called ‘City’ has a modernist illustration by George J.Reilly, ’The Little Old Woman Who Used Her Head’ by Hope Newell (1935),(both in ABC Go!) has delightful black and white drawings by the author. An extract from Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie has the original evocative drawings by Garth Williams – including a colour one – (In Your Own Backyard). ‘The Troll’s Daughter’ by Mary Hatch has very frightening, modernist drawings by Irwin Greenberg (Once Upon A Time), and Pearl S.Buck’s story ‘The Big Wave’ with its delicate prints of shores and waves from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, made me very worried about tidal waves as a child. (Just Around The Corner). Harvest of Holidays is the most American volume, including not only Lincoln’s birthday and John Greenleaf Whittier’s rousing poem about Barbara Frietchie, but five stories about Hanukkah. (This was the first time I realized that Jews had a modern identity in the world.) Roads To Greatness has a piece on African-American nineteenth-century activist Mary McLeod Bethune as well as one on Florence Nightingale; among the other inspiring figures are Marie Curie, Michelangelo and Louis Armstrong. Call of Adventure has an extract from the writings of science-fiction writer Robert Heinlein as well as a really frightening (to me) piece from Elizabeth George Speare’s The Witch of Blackbird Pond about a girl caught up in the Salem Witch Trials. Gifts From The Past has chapters from Twain, Cervantes, Swift, Austen, Allen Poe and may others. Through all the volumes are chapters from authors I would never have heard of otherwise – Sydney Taylor, Cornelia Meigs, Rachel Field. My first introduction to L.M.Montgomery (a life-long favourite) came in Just Around The Corner, where ‘Anne’s Confession’ is taken from from Anne of Green Gables. My least favourite volume was always Legends of Long Ago, but looking at it now I’m impressed at how it gives equal status to classical Greek and Roman stories and American Tall Tales about characters like Johnny Appleseed; their Irish folktale isn’t great, but even as a child I realized that you can’t have everything. (There’s very little about Ireland in any of the volumes, though William Allingham’s ‘Up The Airy Mountain’ is presented with vivid illustrations by Boris Artzybasheff in ABC Go!)

The series editor of these books was Margaret E.Martignoni, ‘Former Superintendent Work With Children Brooklyn Public Library, ‘ assisted by Dr Louis Shore, from Library school, in Florida, and Harry R.Snowden Junior. All the actual volumes were edited by women in library work around the United States. A critic could point out straightaway that the women are ‘relegated’ to the children’s section, and I know I should now look at the encyclopaedia ‘proper’ and see how many female contributors there are, but I don’t feel like going down that road today. Education is not relegation, it is power and privilege beyond belief. And women’s largest educational contribution has, arguably, been made in public libraries rather than schools or universities.

These volumes, like libraries, are educational in the very best sense of the word – encouraging free exploration, introducing new places and ideas, visually stimulating, with a message that people to grow and to change, that the joy of learning and reading is for everybody. But life, while it is often colourful and enchanting, is also harsh and sometimes frightening – as some of the stories I mentioned above would suggest. The old lady in ‘The Old Lady’s Bedroom’ from George MacDonald’s The Princess and the Goblin (Magic In The Air) is judgmental and demanding. In Roads To Greatness, Cornelia Meigs’ story of the Alcotts’ misery and near-starvation when their father converts to an extreme religion is not softened at all. The best story about little-girl bullying that I have ever read anywhere is Eleanor Estes’ ‘The Hundred Dresses’ (1944), about a Polish immigrant girl, Wanda, and Peggy and Maddie, the two ‘nice’ American girls who persecute her relentlessly. ‘Bright April’, by Marguerite di Angeli (1946), in the same volume (In Your Own Backyard), is about an African-American family and the prejudices they encounter, but the self-belief that carries them through. African-Americans, Puerto-Ricans, American Indians, Jews, Mexicans and other North American ethnicities feature quite regularly and matter-of-factly throughout all ten volumes. Diversity isn’t celebrated so much as taken for granted.

Also in the volumes are historical fiction, sea-faring stories, stories about sporting endeavours, friendships, children striking out on their own, tricksters and villains as well as role models. But I sometimes find myself leaving through them simply for the distinctive illustrations. If you find this set of books anywhere in a second-hand bookshop, snap them up. If you see them taking up ‘book-space’ in a pub or restaurant, offer the owner money for them. They are collectors’ items. Remember where you heard it first!

CLEAR CLASSICS BLOG is about books I love, with a bias towards the early to mid-twentieth century.

RECENT READS:

Harriet Baker, Rural Hours: the country lives of Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Townsend Warner and Rosamund Lehmann. (London: Allen Lane 2025). What I enjoyed most about this book was not so much the stories of the authors themselves, but the domestic details about the rural houses they lived in occasionally or temporarily from the ‘Teens to the 1940s – how they coped for water, power, how many rooms they had, and the servants or ‘dailies’ they employed. Because there was so much dependence on local people for food, groceries and for necessities like water and power/fuel, writers and artists and blow-ins generally couldn’t isolate themselves from the communities in which they lived, in a way that they can today. VW and STW found themselves playing important roles in village life, especially during wartime, and if they made the odd snobbish comment, I’m sure the villagers’ comments on them were equally choice. Their personal relationships were complicated. VW’s husband Leonard was a man that people of my mother’s generation would call a ‘saint’, but STW’s lover, who ousted Sylvia from the house to instal her new lover, was so nasty that I’m not even going to mention her name. And if I was disgusted at RL, who kept Cecil Day-Lewis from his wife and small children every weekend during the war, my satisfaction when she (RL), was dumped, along with his wife, for an entirely new woman, was tempered by indignation that the famous poet suffered no consequences whatsoever for his selfishness . (The repellent male literati of that era are described for all to read about in D.J.Taylor’s Lost Girls: love and literature in wartime London ( Constable 2019). ) But it is the texture of everyday life – tablecloths, saucepans, armchairs, water pumps, vegetable gardens – which is the most fascinating element of Baker’s book, making me wonder whether the material culture of peoples’ lives is, in the end, more historically revealing than their personal relationships.

Leave a comment